Smoking refers to inhaling smoke from cigarettes or hookah pipes. Pakistan has ranked 15 among tobacco-producing countries across the globe (CDC, 2001; WHO,2015). As Butti (2010, cited in Latif et al, 2017, p. 240) estimates, smoking will be “the leading cause of preventable deaths and it kills more than 5 million people worldwide each year”. It is predicted that this figure will reach over 8 million by the end of 2030 if the government does not take significant steps to stop smoking across the globe. This is because tobacco becomes the severe cause of more than 25 harmful diseases, especially lung cancer is notorious as a result of smoking (Mohsin, 2005, p. 1111). Over the last few decades, smoking rates have increased among teenagers in Pakistan (Aslam and Bushra, 2010). The purpose of this research is to identify why smoking rates remain high among teenagers in Pakistan. It will be argued that smoking rates remain high due to social factors, failure of anti-smoking campaigns, and non-implementation of the legal framework in Pakistan. This study has been divided into three sections. The first section will explore the social issues and pressures of smoking among the young generation, the second section deals with the failure to implement WHO anti-smoking campaigns, and finally, the link with the non-implementation of the legal framework will be discussed.

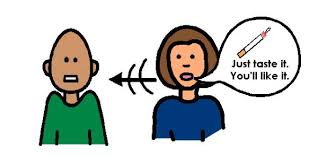

Pakistan global health survey data confirms that 40% of adolescents begin smoking before the age of 10. It is essential to identify that how teenagers start smoking in their initial age. Social factors including peer pressure and domestic impact on the smoking rates which remain high among teenagers in Pakistan (Shaheen et al, 2018). Rozi et al (2005, p. 498) concede that most of the young generation are influenced by their peers and several studies have been indicated that teenagers establish the habit of tobacco in their immature age (Schepis and Rao 2008; Kelder et al, 1994; Zaidi et al, 2011). Potentially, this means that both young genders (boys and girls) develop the habit of smoking from their peers owing to a lack of awareness about the pitfalls of smoking whether they are the inhabitants of urban or rural communities. Also, Kelder et al (1994) and Zaidi et al (2011) admit that due to lack of awareness teenagers are encouraged by smokers and they assume that smoking is an exciting habit. In addition, Shaheen et al (2018) agree that smokers learn the essential techniques of smoking after motivating by their associates and they develop addiction quickly. Similarly, Rozi et al, (2005 p.502-503) claim that 50% of youth start smoking habitually after sharing the cigarettes with their peers and 50% of teenagers purchase tobacco from their pocket money. It appears that smoking habits may vary widely among teenagers in the state, and it might be the case that due to low prices on tobacco products (Ganatra et al, 2007, p. 1366), wealthier teenagers may prefer to purchase cigarettes from their pocket money whilst poor teenagers may prefer to share tobacco with their peers.

The domestic impact could be another leading social factor of smoking which performs a significant responsibility to promote young smokers in Pakistan (Nizami et al, 2011; Shaheen et al, 2018). These researchers also found that because of nicotine in cigarettes, teenagers assume it reduces anxiety and stress. Therefore, they begin smoking before their adulthood. It is probable that some of the youth smoke as a result of their household worries, especially the orphaned young generation smoke to resolve a conflict about their basic necessities of life because they cannot accomplish their fundamental needs without their parents. As Pierce (1987, cited in Pattan et al, 1996 p.1) observed, stress is reduced because of several experiments after inhaling the cigarette and these experiences become the severe addiction of smoking amongst teenagers and they become regular smokers in their teens. Thus, social determinants develop popularity among youth which play a substantial role to promote smoking rates in Pakistan (Shaheen et al, 2018).

World Health Organisation (WHO) anti-smoking campaigns seem likely to have limited success in Pakistan because of failure in implementation. These campaigns have not had enough impact on the smoking rates amongst the young generation across the country. Pakistan became the signatory member of WHO in 2005 after introducing the protection of The Non-Smoker Health Ordinance in 2002. The purpose of this ordinance was to stop smoking across the country. “National anti-tobacco mass media campaign” was started in Pakistan by the ‘Ministry of Health’. The main objective of this campaign was to make people aware of the pitfalls of smoking on their health. The slogan of this campaign was “tobacco is hollowing you out,” which shows the harmful impact on the organs and tissues (Clark, 2015). World Health Organisation (n.d, cited in, Hussain et al, 2019) strongly suggested that Pakistan may expand the scope of health warnings on both sides of cigarette packs. Also, it can organize many training services in national, health, and educational programs for the elimination of smoking amongst teenagers (Nizami et al 2011, p.198; Rao (2014, p.7). As a result of these recommendations, “Cigarette production” has been established indirectly in the country (Hussain et al, 2019). These researchers also concur that Pakistan still needs to overcome smoking rates which remain high even though these campaigns had some success. It seems that by initiating more campaigns in the country government can get success to decrease the smoking products which are freely available in the country. As Mohsin (2005) evaluates, among 62 countries only UK, India, UAE, and Pakistan passed influential laws controlling tobacco Products. However, the United Kingdom has controlled smoking due to high tax rates on tobacco products and Pakistan could not overcome smoking rates as compared to the UK. Therefore, World Bank Report (n.d.)estimates that more than 30% of the young generation still use tobacco products in Pakistan and lack of success can result from poor administration of departments that are identified to implement anti-smoking campaigns in Pakistan.

Non-implementation of the legal framework is another significant factor which causes smoking rates amongst teenagers in Pakistan to be uncontrolled. According to Tobacco Control Policy (TCP) (2020), ‘smoking is prohibited in all places of public work or use.’ This means, according to the law the use of tobacco is fully banned in all public places. Nonetheless, many teenagers are habitual smokers in public places, especially in public schools. Also, studies evaluate that over 14% of teenagers in various public educational institutes are habitual smokers (Shah and Siddiqui 2015). Similarly, research shows that smoking rates remain high among teenagers in public schools as compared to private schools (Shaheen et al, 2018). These researchers also scrutinise that over 25% of smokers try to stop smoking but 97.4% may not be successful.

Over the last few years, many laws and legislation have been introduced against tobacco across the country in reaction to the promotion of smoking advertisements in the country. In addition, it is clearly mentioned in the TCP (2020) that “Tobacco advertising and promotions are prohibited”. According to The Cigarettes (Printing to Warnings) Ordinance (1979), the Ministry of Health has introduced warnings on cigarette packs to reduce the high rates of smoking amongst teenagers in the country. Also, it has been recommended by the current Government and WHO that tax rates should be expanded by 70% in the country (TCP, 2020). However, WHO (2002, cited in, Zaidi et al, 2011) has analyzed that tobacco control legislation is not addressed against shisha and hookah smoking which has acquired popularity among youth in Pakistan. Lack of laws to control hook smoking can encourage this traditional trend amongst the young generation across the state (Dadipoor et al, 2019, p. 7-8). Additionally, studies endorse that shisha smoking is more injurious to health as compared to cigarette smoking (Shah and Siddiqui, 2015). Pakistan Global Youth Tobacco Survey (PGYTS) (2017) estimated that over 25% of teenagers still use tobacco products such as hookah and shisha and Latif et al (2017 p 240) estimates that cigarette smoking rates are still over 61% in Pakistan. Therefore, smoking rates remain high in the country after introducing the laws and legislation because they do not apply to shish, hookah smoking, and partly due to poor implementation.

To summarise, the main factors of smoking amongst teenagers in Pakistan are social issues, failure of WHO anti-smoking campaigns, and non-implementation of the legal framework. As Zaidi et al (2011) observed, Pakistan has taken many serious steps towards the reduction of tobacco smoking among teenagers across the country such as enforcing bans on cigarette advertising and increasing tax rates (Rs 10 on the pack of 20 cigarette sticks). Nevertheless, smoking rates remain high among teenagers in Pakistan. Thus, it is the responsibility of the government to take significant steps for the reduction of smoking amongst teenagers in Pakistan such as by counseling parents, introducing more anti-smoking campaigns, and increasing the tax rates across the country. Also, administrative departments should accept their responsibilities which are to implement the laws and legislation across the country. Furthermore, most studies have assessed the determinants of only cigarette smoking amongst the young generation in Pakistan. Therefore, it would be interesting to carefully understand the attitudes of shisha and hookah smoking in Pakistan.

References

Anjum Q, Ahmed F, Ashfaq T., 2008. Knowledge, attitude, and perception of waterpipe smoking (Shisha) among adolescents aged 14-19 years. J Pak Med Assoc. 2008;58(6):312.

Anti-tobacco awareness campaign., 2019. Available at: https://nation.com.pk/02-May-2019/anti-tobacco-awareness-campaign-launched [ Assessed April 22, 2021]

Aslam, N. and Bushra, R., 2010. Active smoking in adolescents of karachi, pakistan. Oman medical journal, 25(2), p.142. available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3215500/ [Assessed May 12, 2021]

Bhatti MUD, Choksi HM, Bashir NS,. 2010. Tobacco Knowledge, Attitudes and Trends amongst Staff and Students of University College of Dentistry Lahore, Pakistan. Pakistan Oral Dental J. 30(2):468-72)

Dadipoor, S., Kok, G., Aghamolaei, T., Heyrani, A., Ghaffari, M. and Ghanbarnezhad, A., 2019. Factors associated with hookah smoking among women: A systematic review. Tobacco prevention & cessation, 5. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7205165/ [Assessed April 21, 2021]

Ganatra, H.A., Kalia, S., Haque, A.S. and Khan, J.A., 2007. Cigarette smoking among adolescent females in Pakistan. The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, 11(12), pp.1366-1371. Available at: https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/iuatld/ijtld/2007/00000011/00000012/art00017 [Assessed: April 21, 2021]

Gately and Lain, 2004. Tobacco: A Cultural History of How an Exotic Plant Seduced Civilization. Diane.pp. 3-7. ISBN: 978-0-8021-3960-3.

Musaddique Hussain, A. M. I. I. M. F. R. I. H. Q. B. X. W., 2019. Pakistan: time for stronger enforcement on tobacco control. BMJ.

Available at : https://blogs.bmj.com/tc/2019/12/12/pakistan-time-for-stronger-enforcement-on-tobacco-control/ [Assessed May 15,2021]

Jawad M, El Kadi L, Mugharbil S, Nakkash R,. 2015. waterpipe tobacco smoking legislation and policy enactment: a global analysis. Tob Control. 2015;24(Suppl 1): i60-i65. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051911

Clark. J, 2015. Dhaka. Available at: https://www.bmj.com/content/351/bmj.h5860 [Assessed : May 20,2021]

Kelder SH, Perry CL, Klepp KI, Lytle LL: Longitudinal tracking of adolescent smoking, physical activity, and food choice behaviours. Am J Public Health 1994, 84(7):1121–1126.

Khuwaja AK, Khawaja S, Motwani K, Khoja AA, Azam IS, Fatmi Z,. 2011. Preventable Lifestyle Risk Factors for Non-Communicable Diseases in the Pakistan Adolescents Schools Study 1 (PASS-1). J Prev Med Public Health. 44(5):210 217.

Latif, Z., Jamshed, J. and Khan, M.M., 2017. Knowledge, attitude, and practice of cigarette smoking among university students in Muzaffarabad, Pakistan: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Sci. Rep, 3(9), pp.240-246. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/ [Assessed April 21, 2021]

Mohsin, M., 2005. Anti-smoking campaign in Multan, Pakistan. EMHJ-Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal, 11 (5-6), 1110-1114. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16761682/ [Assessed April 22,2021]

Nizami, S., Sobani, Z.A., Raza, E., Baloch, N.U.A. and Khan, J., 2011. Causes of smoking in Pakistan: an analysis of social factors. Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association, 61(2), p.198.

Pakistan Global Youth Tobacco Survey (GYTS). World Health Organization; 2013. Available from: http://www.emro.who.int/images/stories/tfi/documents/GYTS_FS_PAK_2013.pdf?ua=1

The toll of tobacco in Pakistan, 2017. Available at:https://www.tobaccofreekids.org/problem/toll-global/asia/pakistan [Assessed April 22, 2021]

Patton, G.C., Hibbert, M., Rosier, M.J., Carlin, J.B., Caust, J. and Bowes, G., 1996. Is smoking associated with depression and anxiety in teenagers? American journal of public health, 86(2), pp.225-230. https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/abs/10.2105/ajph.86.2.225 [Assessed April 21, 2021]

Pierce JP, Levy SJ. Smoking and drinking problems in young Australians. MedJAust. 1987; 146:121-122.

Siddiqui S., 2012. Patterns of Lung Cancer in North-Western Pakistan. Saarbrücken: LAP Lambert Academic.

Schepis T, Rao U: Smoking cessation for adolescents: a review of pharmacological and psychosocial treatments. Curr Drug Abuse Rev 2008, 1(2):142.

Shaheen, K., Oyebode, O. & Masud, H. 2018, “Experiences of young smokers in quitting smoking in twin cities of Pakistan: a phenomenological study”, BMC public health, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 466-466.Available at: https://doaj.org/article/35de6d38c4cd421e8190762fcaff8cee [Assessed 15-04-2021]

Tobacco Control Policies Pakistan,.2020. Available at: https://www.tobaccocontrollaws.org/legislation/factsheet/policy_status/pakistan

[Assessed April 22,2021]

Shah, N. and Siddiqui, S., 2015. An overview of smoking practices in Pakistan. Pakistan journal of medical sciences, 31(2), p.467.Available at:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4476364/ [Assessed April 21,2021]

Rao, S., Aslam, S.K., Zaheer, S. & Shafique, K. 2014, “Anti-smoking initiatives and current smoking among 19,643 adolescents in South Asia: findings from the Global Youth Tobacco Survey”, Harm reduction journal, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 8-8. Available at: https://harmreductionjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1477-7517-11-8#citeas [Assessed 15-4-2021]

Rozi, S., Akhtar, S., Ali, S. and Khan, J., 2005. Prevalence and factors associated with current smoking among high school adolescents in Karachi, Pakistan. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health, 36(2), pp.498-504.

WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Available at: http://www.who.int/ fctc/en/ [Assessed 15 May 2021]

Zaidi, S.M., Bikak, A.L., Shaheryar, A., Imam, S.H. and Khan, J.A., 2011. Perceptions of anti-smoking messages amongst high school students in Pakistan. BMC Public Health, 11(1), pp.1-5.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/1471-2458-11-117 [Assessed April 21, 2021]

Discover more from Research Initiatives

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.